Brownsville, Texas — Before our WFAA crew got to the border Monday afternoon, we knew the basics about what was happening here: Hundreds of immigrant children were being held at facilities in the Rio Grande Valley, and some of those children had been separated from their families at the border.

And that's still the case. Children remain in several facilities along the border, despite President Donald Trump's executive order Wednesday, halting family separations.

But what we've learned – myself, reporter Rebecca Lopez and photojournalist Martin Doporto – has been less about the nuts and bolts of the story and more about hearing stories on what has become a crisis for many families.

We heard emotional stories from families who crossed the border

One of our

most insightful interviews was with a

family that hadn't been separatedat the border. Instead, Nelson Lara was detained, given an ankle bracelet and released, along with his one-year-old daughter.

We met Lara, 22, and his daughter at the Catholic Charities shelter in McAllen on Monday night. They had traveled to the U.S. border from Honduras. Lara and other adults at the shelter avoided jail because a holding facility was at capacity, Sister Normal Pimental, who runs the shelter, told us.

We had gone to the shelter to interview Pimental, hoping to learn more about the immigrant children.

But when we walked in, the room was full with immigrant families: mothers and fathers sitting in small blue chairs and holding their children. Older kids played with toys. A young boy walked over to us, curious about our camera equipment.

We interviewed Pimental. Then Rebecca asked Lara if we could interview him and he agreed, in Spanish.

He wore an Aeropostale polo shirt, jeans and dusty black shoes. They were the only clothes he brought with him. He fed his daughter Cheetos and sipped on a Capri Sun.

He told us how "you can't even make enough money for food" in Honduras, so he left his home country to work in the U.S.

Other families appeared to have few belongings, other than a tote bag of essentials, like food and batteries, that the Catholic Charities provided. While these families were still together, they gave us a glimpse who these immigrants are – and who's being affected by the family separations.

After interviewing Lara, we left McAllen for the hour drive back to Brownsville, where Rebecca did a live shot for the 10 p.m. news at a former Walmart that is housing hundreds of immigrant boys.

If you saw this on TV, then you probably already know: The place looks exactly like any other Walmart, aside from new signage and security barriers around the parking lot. The facility is run by Southwest Key Programs, a nonprofit under federal contract.

Like everyone else, we knew about this facility. The Department of Health and Human Services released photos and video from inside the facility, and Southwest Key gave a media tour.

Volunteers told us about caring for immigrant girls and toddlers

But that facility only held boys. We hoped to understand where

immigrant girls and toddlers were being held.

No photos or videos from these facilities had been released and they apparently weren't as large – or as visible – as the former Walmart location, which sits off a busy intersection. Where were these facilities and what did they look like?

Rebecca found an address for a facility in Combes, about 20 miles northwest of Brownsville. Off a two-lane highway in a somewhat rural area, the two-story building had a small playground and tall fences around the yard. An employee asked us to leave when we approached the front gate. We weren't surprised – it was private property, and most immigrant facilities have been heavily restricted.

A few minutes later, a Combes police officer arrived, apparently to make sure we weren't on the facility's property. But he didn't have a problem with us – and a crew from MSNBC – filming on the road about 100 yards from the entrance.

In interviews outside of the facility, Ofelia De Los Santos and Benigo Palacios, a deacon with the diocese, gave heartfelt accounts of ministering to the young girls inside.

"Every single child gets up and begins to pray to God in a loud voice, 'Please, God, send me back to my parents,'" De Los Santos said.

After Trump's executive order, questions remain about what happens now

After our interviews, the skies opened up.

We headed to a CVS Pharmacy to buy umbrellas (no luck), then found a gas-station awning for Rebecca's 5 p.m. live shot.

On Wednesday morning, we had planned to go to the border crossing in Brownsville, where families on the Mexico side were still waiting for asylum to enter the U.S.

Then came the big news: Trump would be signing an executive order to stop family separations. So we shifted our focus two things: reaction to the executive order and what would happen next.

Would families be reunited? How long would it take? Who would coordinate the reunification process? What would happen to families at the border now?

These were all questions we didn't know – and as the afternoon went on, we found out that not many people in the Valley knew either. Officials with the Diocese weren't sure when the reunification would happen. Southwest Key, which operates the facilities, hadn't been providing information.

Our colleague Jason Whitely – who's been covering the story from Tornillo, near El Paso – later reported that the children would be staying with their parents at family detention centers but that the reunification could take weeks.

One thing was clear: Advocates in the Valley were happy. Trump's executive order "was like God had spoken," De Los Santos told us.

"I prayed for respect for one another," Pimental told us at the Catholic Charities shelter, "for protection for people who need respect and cared for, not harmed."

For Pimental, the executive order "was a step in the right direction," she said.

At the same time, there was still a work to be done: A line of families of from Guatemala arrived at the shelter, carrying their belongings in plastic sacks and trash bags.

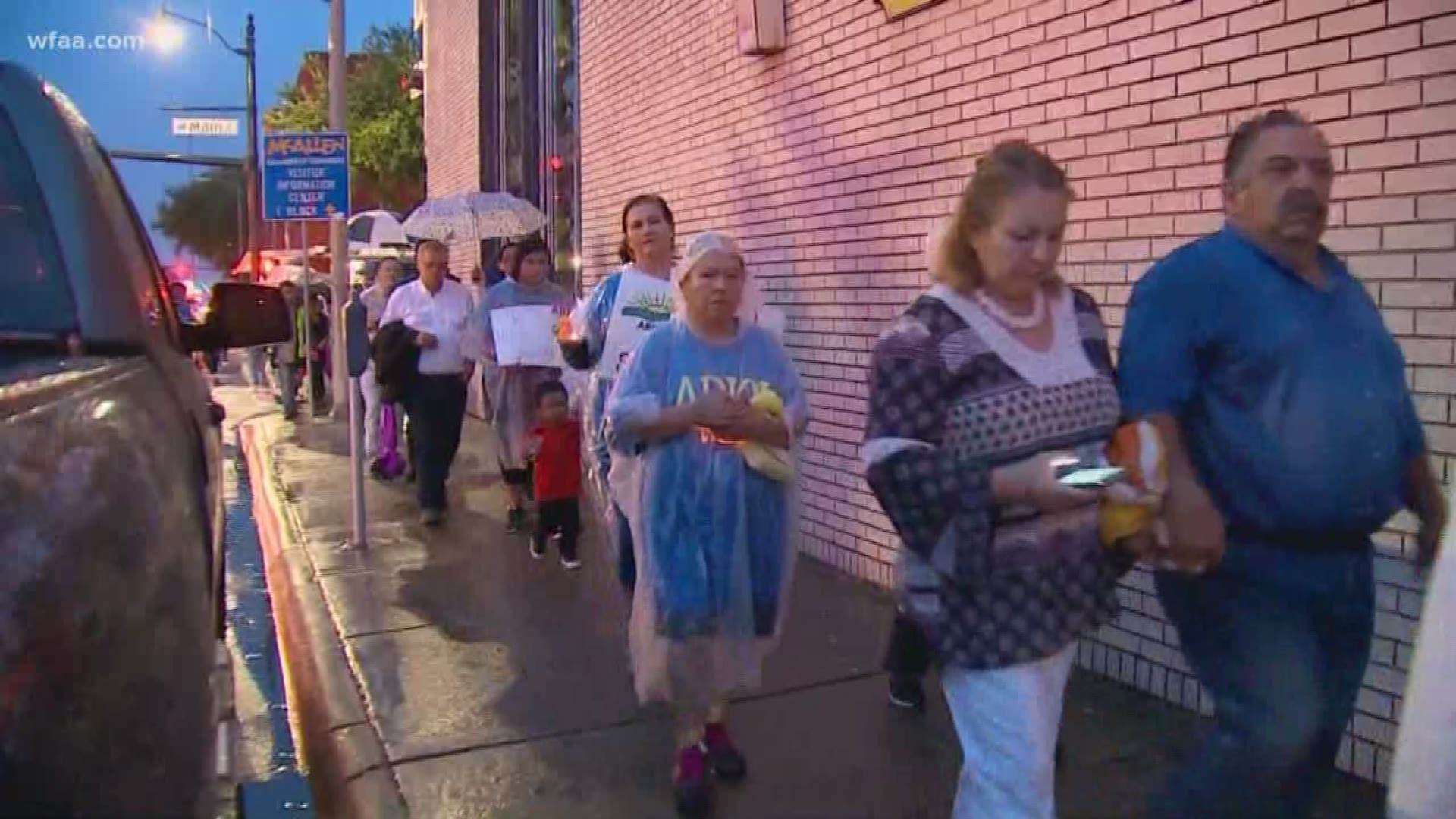

Later Wednesday, we covered a prayer vigil for the immigrant children in McAllen. I met two men, Elias Melchor and Daniel Carranza, from nearby Edinburg. They were 20, only a few years older than some of the teens separated from their families.

I started a Facebook Live and walked with Melchor and Carranza as they marched in the rain with hundreds of others to a nearby courthouse. They talked about growing up in the Valley, where some of their friends' parents "don't have papers," Melchor said.

Melchor and Carranza have marched over DACA and the Texas Sanctuary Cities bill, both issues that drew widespread media attention. This week, the media had descended on their hometown, reporters and cameras everywhere. But immigration issues aren't just faraway headlines in the Valley.

"If there's more vigils, more walks, we'll more than likely be here," Melchor said. "Because it's who we are. It's how we were raised. It's how we are going to be for a while."