FRISCO, Texas — Dave Myers sat down in a chair inside his senior living facility and leaned his cane on a desk.

“Let me get rid of this thing,” he said, before retelling the stories he’s told many times before. But they are stories we still need to hear.

“I think in order to solve the problems we have in this country between races and cultures you have to –– well, 'How do I want to say this?' You have to do things that make yourself uncomfortable. We’re comfortable with people like us, and you have to make yourself uncomfortable,” he said.

Myers knows a thing or two about being uncomfortable.

He'd been warned his actions during the 1960s civil rights struggle could get him jailed, beaten or even killed. But he protested anyway.

“I kept wondering, ‘Am I ever going to see my family again?’ I had a new nephew born while I was in and I’d never seen him,” Myers said.

Myers is white, but he went to an all-black university in Ohio because it was the only school that offered financial aid.

He was born poor to a farming family in a small Indiana town where there were only a few black people.

“I’d never gone to school with a black student until I was a junior in high school,” he said.

Myers eyes were opened when he arrived at Central State.

“It changed my world,” he said. “I was living with an entirely new culture, new language, music that I’d never heard before playing all the time in the dormitory. It was an entirely different lifestyle that I’d never lived before.”

“I went to the library a lot because I liked to read the newspaper,” he said. “There was this rack of big city newspapers: St. Louis, Chicago, Washington, Dayton, Indianapolis. But then there was another rack that had papers like the Baltimore Afro-American and the Chicago Defender – black newspapers.”

“That gave me an entirely different slant on the news than the big city papers did. I learned a lot from that.”

He remembers being at his mom’s home in Indiana on Mother’s Day weekend of 1961 when he saw coverage of a bus burning in Alabama.

Young men and women – black and white – were making a statement by traveling via bus to the south. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled it unconstitutional to allow segregated buses on interstate travel.

The activists called themselves, Freedom Riders.

And when they arrived in Alabama, they were met with angry mobs.

When a call went out for more Freedom Riders to join the effort, Myers headed south.

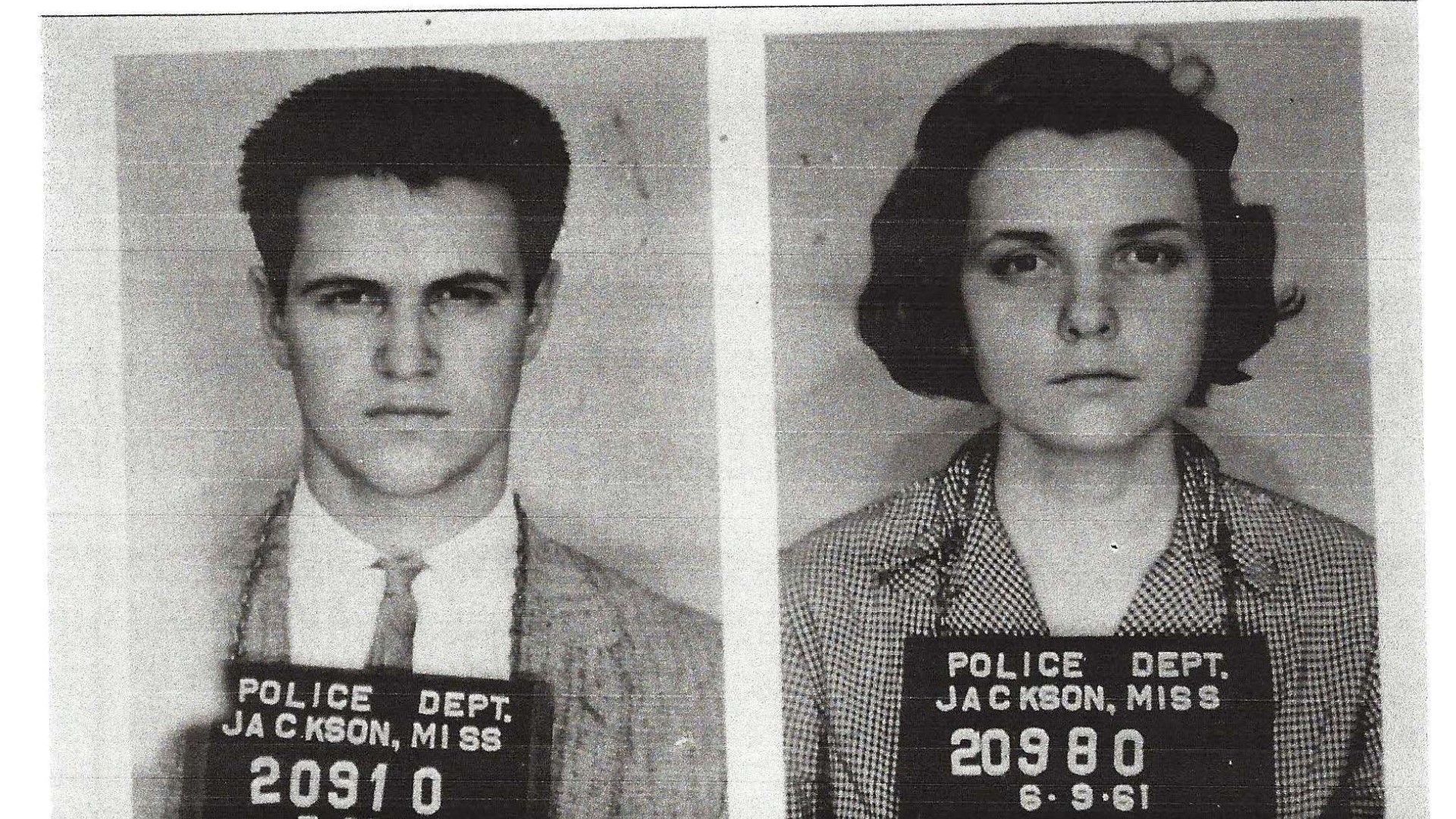

He rode a bus with an integrated group to a transit station in Mississippi. They walked past a “whites only” sign, sat down and refused to leave. Police arrested them and charged them with breaching the peace.

“It seemed to me like so little compared to what most black people were going through for 100 years in the United States,” he said.

Myers spent 30 days in the Mississippi state prison. And until he received a letter from her, he didn’t know his girlfriend from Central State, Winonah Beamer, was in prison as well.

Like Myers, she was white and from a poor family and Central State was the only university to offer financial aid.

She had joined another group of Freedom Riders and was arrested a few days after Dave.

The couple eventually married. Myers made a career in journalism. He spent almost 30 years as a television news photographer in Ohio.

Exposure to people they didn’t know ignited a quest for equality. It took them to places they’d never been, and introduced them to people Dave still can’t believe he met – like Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Meeting him on a couch in the Alabama home where Myers took refuge in the days before he joined the Freedom Riders was “the surprise of a lifetime.”

“I met him on three different occasions after that,” he said.

The Freedom Riders have been the subject of books and documentaries. They were even featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show on the 50th anniversary.

Winonah passed away a couple years ago and Myers relocated to Frisco to be near family.

He is in the early stages of Parkinson’s Disease and now relies on a walker to navigate the halls at Mustang Creek Estates.

His body might have changed. But his mind never will.

“What a life it’s been,” he said. “I’m not as proud of what I did as the people I did it with.”

More WFAA Feature stories: